|

THE STORY

| Robert the Bruce

Along with William Wallace, Robert the Bruce is one of Scotland's greatest historical heroes. His reputation as a determined and courageous man who endured immense hardship before winning the great battle at Bannockburn is a deserved one. However, for many, his reputation is affected by his ceaseless manoeuvring and changing loyalties. His victory at Bannockburn, re-establishing Scotland's independence, was a monumental event due to his dedication, perseverance and military skill. However, he is not regarded by all Scots with the unquestioning respect and admiration that is shown to William Wallace.

|

Robert the Bruce Statue at Bannockburn © The National Trust for Scotland

|

Loyalty

|

Bruce maquette by Charles d'Orville Pilkington Jackson © Glasgow Museums and Art Galleries

|

Unlike Wallace, who stayed true to re-establishing Scotland's independence and loyal to one figure: King John Balliol, Bruce was a more complex individual. He reportedly changed sides 5 times between supporting Edward I and opposing him. He is reported to have said in 1297, after being ordered to take Douglas Castle by Edward I but then switching allegiances to the Scottish cause, "No man holds his own flesh and blood in hatred and I am no exception. I must join my own people and the nation in which I was born." Many Scottish nobles held lands in England and were scared of losing them, a fact that Edward I used to his advantage.

|

Comyn Gone

After waging a campaign in the southwest in the early 1300s, Bruce surrendered to Edward I in 1302, fearing the possible return of John Balliol to Scotland as King. He waited and then made his move for the throne in 1306. In February he met with John Comyn, his rival for the crown, in Greyfriar's Church in Dumfries. An argument broke out and Bruce stabbed and killed Comyn, an event for which he was to be excommunicated from the church. No matter the rights and wrongs of his actions, he had made his move.

|

Murder of Comyn © National Trust for Scotland

|

King Robert I of Scotland

|

The crowning of Robert the Bruce © National Trust for Scotland

|

He and his men immediately started military action against the English forces. They worked their way north, taking castles and attacking where possible using the quick raiding style of Wallace. Bruce had himself crowned King six weeks later at Scone on 25th March and as King Robert I embarked on a journey that would re-establish Scotland's independence. In May, King Edward I vowed to get revenge for the death of Comyn, swearing "before God and the swans". (Swans were regarded as a further way of binding a person to their oath).

|

Setbacks

| After his coronation Bruce suffered large setbacks, losing in June at Methven near Perth and at Dail Righ (Dalry), near Tyndrum, in August. His forces were severely weakened and down to as few as only several hundred men. He was forced to flee. He went as far as Rathlin Island, only 6 miles off the coast of what is now Northern Ireland. Members of his family were taken prisoner by the English. The woman who had crowned him, the Countess of Buchan, and Bruce's sister Mary were placed in cages and hung from the turrets of castles. They were not released until 1310. |

Countess of Buchan by Stewart Carmichael © Dundee City Council, McManus Galleries

|

|

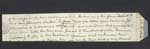

Fragment from original manuscript of Walter Scott's "Tales of a grandfather" © Edinburgh University Library

|

It is around this time that the legend of Bruce and the spider comes from. He supposedly gained inspiration to keep going from watching a spider attempting again and again to make its web. While the legend is strong, the factual basis is weak and inconclusive. There are at least 3 caves that claim to have been the location: on Rathlin Island, at Roslin Glen, and on Arran. The story actually comes from "Tales of a Grandfather" written by Sir Walter Scott in the 19th century. |

Road to Victory

|

Loudoun Hill © Douglas Skelton

|

He returned in February 1307 to Carrick and embarked on a more successful campaign, winning at Loudon Hill. As a result of his successful campaign, Bruce was soon able to govern, holding his first parliament in 1309 in St Andrews. Confident and in a position of strength, he sent the "Black Douglas," Sir James, to England to wage war in England itself.

|

| Edward I attempted to make one more offensive attack on Scotland, but he died suffering from dysentery near the Solway Firth. A memorial marks the spot where he died, which ironically has many thistles growing around it. His son, the Prince of Wales, became King Edward II but was not of the same fighting character as his father and did not pursue Bruce as Edward I would undoubtedly have done. |

Edward I Monument © Peter Nicholson & Peter Armstrong

|

|

Bruce's campaign involved his use of the surprise attack, usually by night. He took castles not by the normal means of lengthy sieges, but by stealth and small numbers of men. For example in 1313 he personally led the night-time taking of Perth, by swimming the moat and then scaling the walls by using rope ladders. His tactics proved very effective and by 1314 Bruce had regained all castles in Scotland from English hands and only one remained: the crucial castle at Stirling. |

THE BATTLE OF BANNOCKBURN, 1314 23rd June - Day One

|

Aerial view of Battle of Bannockburn © National Trust for Scotland

|

An agreement was made that should Stirling Castle not be relieved by midsummer 1314, it would be handed over to Robert the Bruce. Edward II raised a large army and marched to get to the castle before this time. Robert the Bruce realised the importance of the castle and although wary of a pitched battle, met Edward's army at a place on the southern approaches to Stirling Castle, at Bannockburn.

|

Edward's army had 2,000 cavalry and about 17,000 foot soldiers and bowmen. Bruce's opposing force numbered only about 5,500. Bruce organised his army well to block Edward's advance. Bruce was to use the tactic of the schiltrom as Wallace had done. Some of the English cavalry attacked on the first day of the battle, the 23rd June, but were repelled by the spears of one of the schiltroms.

|

Battle of Bannockburn © National Trust for Scotland

|

|

Robert the Bruce slaying de Bohun © Patrick Benham

|

Also on that day an incident occurred that showed Robert the Bruce's bravery and personal skill in combat. He was organising the forward lines of his army when some English knights on a patrol spotted the king. One of them, Sir Henry De Bohun, charged at the King with his 12 foot long lance. Bruce waited until the right moment, avoided the lance, rose up in his stirrups and killed De Bohun with his battle-axe in one blow to the head, slicing through his helmet. Bruce's action on the eve of the main battled acted as an inspiration to his army. When rebuked by his noblemen for getting into such a dangerous situation, he shrugged it off, complaining that he had lost a good battleaxe!

|

24th June - Day Two

|

Medieval Axe © Granite Productions

|

The English morale was low as a result of their poor showing the previous day. Because of the large difference in sizes between the two armies, Bruce was advised to remove his army from the field to prevent it from being destroyed and then carry on the guerrilla war as before. However Bruce had decided that there was no going back and this was to be the time and place for a decisive victory.

|

The Scots advanced on the English position. In sight of their enemy they fell to their knees to pray. Edward II is reported to have gloated saying "They kneel for mercy!" He was to be proven wrong. The English cavalry charged, but came up against a schiltrom. The Scots responded by moving to attack, with the spearmen pushing forwards. English archers began to have some success but Robert the Bruce instructed his cavalry to charge on them.

|

Painting of a Scottish schiltrom © National Trust for Scotland

|

|

Bannockburn Room, Peebles Hotel Hydro, Peebles (detail) ©Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum

|

Bruce's reserve force was deployed. The battle was now raging, with most of the armies engaged. It became so confused and compressed that the English archers' arrows fell on their own men. The battles was turning in Bruce's favour. Edward II left the field, heading for the castle and safety. The English army were wavering and it was here that the famous intervention of the "camp followers" happened. These 2,000 men were not trained soldiers, but men who had little in the way of proper weapons. They rushed onto the field and at the sight of them coming, the English army broke apart. The Scots pursued them. So many English troops were killed in the Bannock Burn itself that it was said a man could cross it without getting wet. Edward II was refused entry to the castle and headed for Dunbar and escape.

|

Declaration of Arbroath

After Bannockburn, Bruce was able to rule without fear of large-scale Engish invasion. He continued raids on northern England, and expeditions to Ireland were also carried out. A religious man, he was still excommunicated from the church for the murder of John Comyn in 1306 and it was partly to redeem this situation that one of the most famous and often-quoted documents in Scotland was written.

The Declaration of Arbroath was written in 1320. The most famous section has been much quoted as a statement of national resolve: "As long as but a hundred of us remain alive we will never be subject to English domination, because it is not for glory nor riches nor honours that we fight, but for freedom alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself." It is taken to be the first statement of a nation's independence.

|

Representation of Scottish noblemen signing the Declaration of Arbroath © National Trust for Scotland

|

Brave heart

Although Bruce had secured victory at Bannockburn in 1314 it would take another 14 years for the acceptance by England of Scotland's independence. This was achieved in the Treaty of Edinburgh (ratified in Northampton) in 1328. By this time Bruce was very ill, possibly with leprosy. He lived only for one more year, and died safe in the knowledge he had achieved his goal of re-establishing Scotland's independence and its own monarchy. His body was buried in Dunfermline Abbey and his embalmed heart was taken on the Crusades in the Middle East by the faithful Sir James Douglas, who had fought alongside him in his many campaigns. Douglas was killed and Bruce's heart was returned to Scotland, where it was buried at Melrose Abbey.

|

Casket containing Robert the Bruce's heart © Crown Copyright reproduced courtesy of Historic Scotland

|

|

|